Franz Xavier Winterhalter Paintings

Franz Xaver Winterhalter was a German painter and lithographer, known for his portraits of royalty in the mid-nineteenth century. Born on April 20, 1805, in Menzenschwand, Grand Duchy of Baden (now part of Germany), Winterhalter came from a family of farmers. Despite his humble origins, his artistic talent became apparent early on. He initially studied painting at the Academy of Arts in Munich and later moved to Karlsruhe to study under Karl Ludwig Schüler.

Winterhalter's career took a significant turn when he went to Italy in 1833 to further his studies. It was during his time in Italy that he developed his distinctive style of portraiture that would later make him famous. After returning to Germany, he caught the attention of Grand Duke Leopold of Baden, who became his first major patron. His reputation grew, and by the 1830s, he was painting portraits for the aristocracy across Europe.

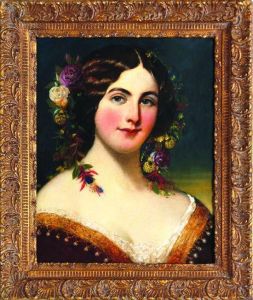

In 1835, Winterhalter moved to Paris, where he quickly became the preferred portrait painter of King Louis-Philippe's court. His success in France opened the doors to commissions from other European monarchs, including Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, who admired his work greatly. Winterhalter became renowned for his ability to capture the elegance and opulence of his subjects, often portraying them in sumptuous settings with a touch of Romanticism.

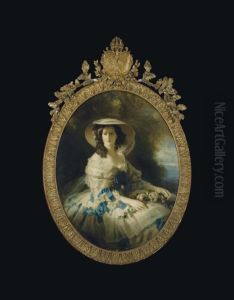

Throughout his career, Winterhalter painted over 1,000 portraits. His most famous works include portraits of Empress Eugénie of France, surrounded by her ladies in waiting, and Queen Victoria in various representations. Despite his popularity, Winterhalter's work was sometimes criticized for its perceived superficiality and emphasis on aesthetic appeal over depth.

Winterhalter remained in demand until his death in Frankfurt on July 8, 1873. Although his work fell out of favor in the early 20th century, regarded as too representative of the old social orders, there has been a resurgence of interest in his art in recent decades. Today, Winterhalter is recognized as one of the foremost portraitists of the 19th century, celebrated for his ability to blend realism with a certain ethereal quality that captured the spirit of his era.