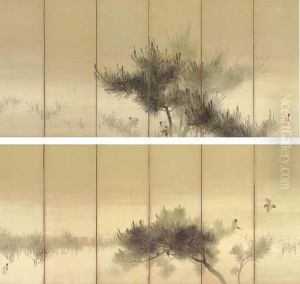

Tsuji Kako Paintings

Tsuji Kako was a prominent Japanese painter and calligrapher, born in 1870 and passing away in 1931. He is particularly known for his contributions to the Nihonga style, a term that refers to traditional Japanese painting techniques and subjects. His works are characterized by their delicate beauty, traditional motifs, and a deep appreciation for the natural world, reflecting the aesthetic preferences of Meiji, Taishō, and early Shōwa period Japan.

Kako initially trained under the guidance of Suzuki Hyakunen, a well-regarded painter of the time, which deeply influenced his early career and style. Tsuji Kako's artistic journey was marked by his ability to blend traditional Japanese painting techniques with a sense of modernity that was emerging in the Meiji period, as Japan opened up to the Western world. This period was marked by significant cultural shifts, as Japan sought to balance its rich traditional heritage with new influences and technologies from the West.

Throughout his career, Kako was deeply involved in the artistic community. He was a member of the Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin), a prestigious organization that played a crucial role in the development and promotion of Nihonga painting. His affiliation with this institute connected him with other leading artists of his time, allowing for a rich exchange of ideas and furthering his evolution as an artist.

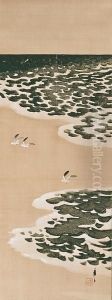

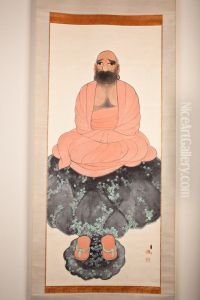

Tsuji Kako's work is celebrated for its elegance and the way it captures the essence of Japanese spirituality and aesthetics. He often depicted landscapes, flowers, and birds, bringing out their beauty through meticulous brushwork and a refined use of color. His paintings not only reflect the technical skills expected of Nihonga artists but also express a deep, poetic sensitivity to the natural world.

Despite his achievements during his lifetime, Tsuji Kako's legacy in the broader context of Japanese art history is somewhat overshadowed by his contemporaries, such as Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunsō, who were also key figures in the development of modern Nihonga. Nevertheless, his body of work continues to be appreciated for its contribution to the genre and its embodiment of the transitional period in Japanese art, bridging the gap between the traditional and the modern. His paintings are held in various collections and museums, both in Japan and internationally, where they continue to be studied and admired for their beauty and historical significance.