Kunisada Iii Hosai Paintings

Kunisada III Hosai, also known as Utagawa Kunisada III, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist who lived during the late Edo and early Meiji periods. Born in 1848 in Edo (present-day Tokyo), he was a pupil of Utagawa Kunisada I, also known as Toyokuni III, who was one of the most popular and prolific ukiyo-e artists of his time. Kunisada III was the adopted son and direct artistic heir of Kunisada I.

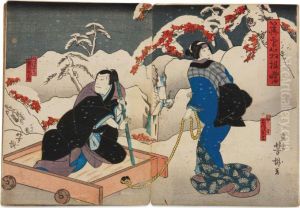

As a member of the Utagawa school, Kunisada III inherited the artistic legacy of not only his master but also the school's founder, Utagawa Toyokuni I. Within this tradition, he initially worked under the name of 'Baidō Hōsai' before eventually taking on the name 'Kunisada' after the death of his master in 1864. His works included a variety of ukiyo-e genres, such as yakusha-e (actor prints), bijinga (pictures of beautiful women), and occasionally landscapes and warrior prints. However, by the time Kunisada III began his career, the ukiyo-e genre was in decline, facing competition from photography and Western art forms, as well as the societal changes occurring during the Meiji Restoration.

Despite these challenges, Kunisada III continued to produce woodblock prints and contributed to the tail end of the ukiyo-e tradition. He is known for his portraits of kabuki actors, which were popular among the urban populace of Edo. His style was characterized by a continuation of the flamboyant and colorful techniques of his teacher, with an emphasis on elaborate patterns and strong outlines. While his work never reached the same level of fame as his master's, he was able to maintain a career as a woodblock print artist through the end of the 19th century until his death in 1920.

Kunisada III's later life coincided with the decline of the traditional ukiyo-e print market. As Japan opened up to the West and modernized, the demand for such prints dwindled. Nevertheless, Kunisada III's dedication to his craft ensured that the Utagawa school's techniques and styles were preserved through a period of significant cultural and artistic transition in Japan. Today, his works are considered part of the historical legacy of Japanese art and offer insights into the cultural and theatrical world of late Edo and early Meiji period Japan.