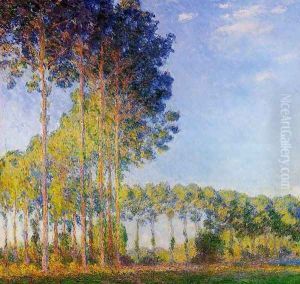

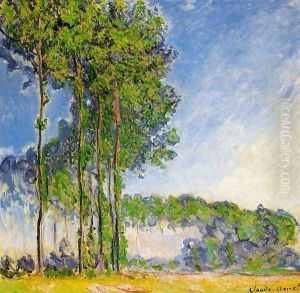

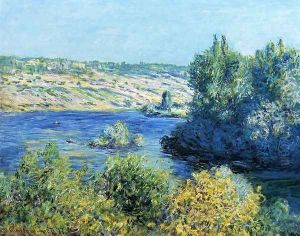

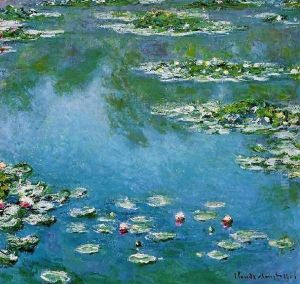

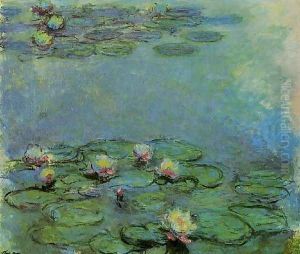

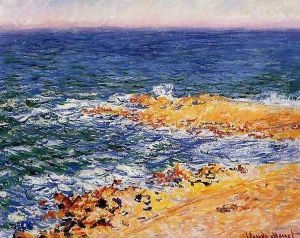

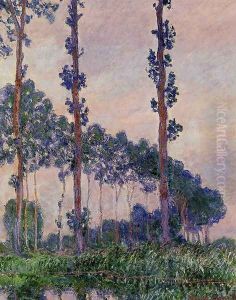

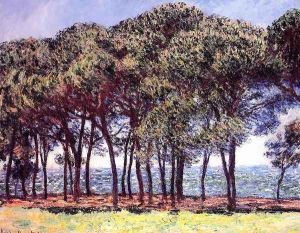

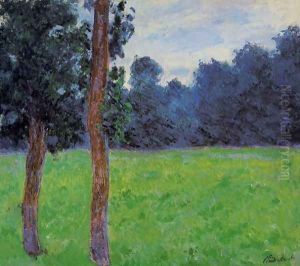

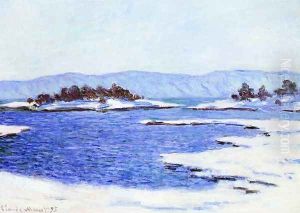

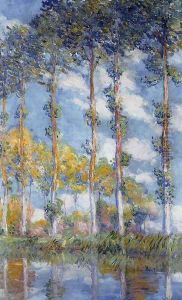

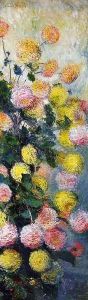

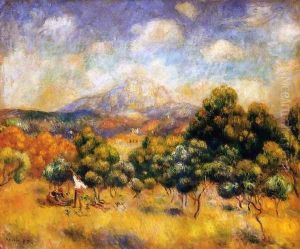

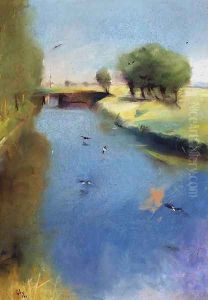

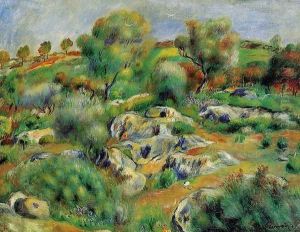

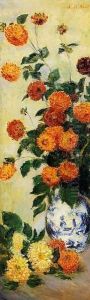

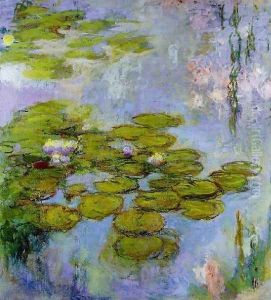

Impressionism Paintings

In 1874, a group of artists called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. organized an exhibition in Paris that launched the movement called Impressionism. Its founding members included Claude Monet,Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, among others. The group was unified only by its independence from the official annual Salon, for which a jury of artists from the Academie des Beaux-Arts selected artworks and awarded medals. The independent artists, despite their diverse approaches to painting, appeared to contemporaries as a group. While conservative critics panned their work for its unfinished, sketchlike appearance, more progressive writers praised it for its depiction of modern life. Edmond Duranty, for example, in his 1876 essay La Nouvelle Peinture (The New Painting), wrote of their depiction of contemporary subject matter in a suitably innovative style as a revolution in painting. Their work is recognized today for its modernity, embodied in its rejection of established styles, its incorporation of new technology and ideas, and its depiction of modern life. Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise (Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris) exhibited in 1874, gave the Impressionist movement its name when the critic Louis Leroy accused it of being a sketch or "impression," not a finished painting. It demonstrates the techniques many of the independent artists adopted: short, broken brushstrokes that barely convey forms, pure unblended colors, and an emphasis on the effects of light. Rather than neutral white, grays, and blacks, Impressionists often rendered shadows and highlights in color. The artists' loose brushwork gives an effect of spontaneity and effortlessness that masks their often carefully constructed compositions, such as in Alfred Sisley's 1878 Allee of Chestnut Trees (1975.1.211). This seemingly casual style became widely accepted, even in the official Salon, as the new language with which to depict modern life.