Heinrich Scherer Paintings

Heinrich Scherer was a German cartographer, geographer, and a Jesuit priest, whose works significantly contributed to the fields of cartography and geography in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Born in 1628 in Dillingen, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, Scherer took vows as a Jesuit in 1647, marking the beginning of a lifelong commitment to education and scholarly pursuits within the order. His academic journey and religious vocation led him to teach humanities in Landsberg and later mathematics and Hebrew in Munich, showcasing his diverse interests and expertise.

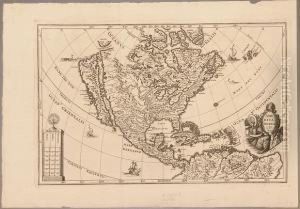

Scherer's most notable contribution to cartography and geography was his publication of the 'Atlas Novus', a comprehensive world atlas that was released in several volumes between 1702 and 1710, soon after his death in 1704. This atlas was distinguished by its unique combination of scientific rigor, elaborate baroque artistry, and overtly religious themes, reflecting Scherer's Jesuit background. The 'Atlas Novus' included maps and geographical descriptions of various parts of the world, with particular emphasis on missions and the spread of Christianity, a testament to Scherer's desire to document the world through a religious lens.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Scherer's work was deeply infused with his Jesuit ideology, often portraying non-European lands as fertile grounds for religious conversion and missionary work. His maps are notable for their decorative elements, including elaborate cartouches and vignettes illustrating indigenous peoples and exotic fauna. Scherer’s approach to cartography was part of a broader Jesuit strategy to use maps and scientific knowledge as tools for evangelization.

Despite his significant contributions to cartography, Heinrich Scherer is a somewhat obscure figure in the history of geography, overshadowed by more prominent contemporaries. However, his work remains a fascinating study for historians interested in the intersection of science, art, and religion during the early modern period. Scherer's maps are not only valuable for their geographical content but also as cultural artifacts reflecting the complexities of European engagement with the wider world during the Age of Discovery. He passed away in 1704, leaving behind a legacy that encapsulates the Jesuit contribution to the scientific and cultural understanding of the world.