Heinrich Ambros Eckert Paintings

Heinrich Ambros Eckert was a relatively lesser-known German painter and lithographer born in the early 19th century. His life, unfortunately, did not span many decades, as he was born in 1807 and died prematurely in 1840. Despite the brevity of his life, Eckert managed to leave a mark on the art world through his artistic endeavors.

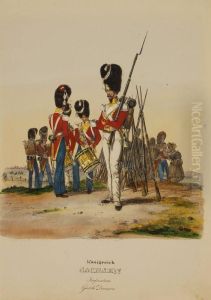

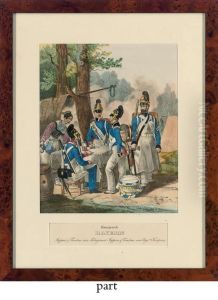

Eckert's work primarily revolved around lithography, a printing process that was gaining popularity during his lifetime. This technique involves creating images on a flat stone surface and using it to transfer the image onto paper. Lithography appealed to artists and printers because it could easily produce many copies of a work. Eckert's lithographs would have included various subjects, from landscapes to portraits, and possibly scenes of contemporary life or historical events, reflecting the tastes and interests of the period.

Although there is limited information regarding his personal life or artistic training, Eckert's active years as an artist would have been during a time of significant cultural and political change in Europe. The 1830s and 1840s were marked by the rise of nationalism, revolutions, and the burgeoning Romantic movement, which influenced the arts profoundly. Artists were beginning to express more emotion in their work, and there was a growing interest in nature, the exotic, and the historical past.

Given the era in which he lived, Eckert would have been exposed to these movements and may have been influenced by other prominent artists of the time. His work would reflect the technical skills and artistic sensibilities of the period, contributing to the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art.

Unfortunately, Heinrich Ambros Eckert's career was cut short due to his untimely death at the age of 33. As a result, his oeuvre might not be as extensive as that of his contemporaries who lived longer lives. Nevertheless, his contributions to lithography and the art of his era remain a part of the historical record. Although not as well-known as some of his peers, Eckert's work would still be of interest to scholars studying the evolution of printmaking techniques and the visual culture of 19th-century Germany.