Gian Cristoforo Romano Paintings

Gian Cristoforo Romano was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, medallist, and engraver, born in 1465 in Rome, Italy. He was part of a family deeply involved in the arts; his father, Isaia da Pisa, was a noted sculptor as well, providing Gian Cristoforo with an environment rich in artistic tradition from an early age. Despite the shadow of his father's reputation, Gian Cristoforo emerged as a significant figure in the Italian Renaissance, known especially for his portrait sculptures and medals which capture the nuances of human expression and the ideals of the period's aesthetics.

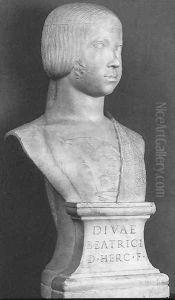

Romano's career flourished in the courts of Italy's leading families, where he was highly sought after for his skill in sculpting portraits and religious subjects. He spent a significant portion of his career in Milan, under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, where he was involved in the decoration of the Certosa di Pavia and the Duomo of Milan. His work during this period reflects the Lombard architectural and sculptural traditions, blending them with his unique style characterized by elegant realism and attention to detail.

By the late 15th century, Gian Cristoforo had established himself as a master of medal-making, a form of art that was gaining popularity among the Italian elite for its ability to immortalize the features and achievements of its subjects. His medals are considered among the finest examples of the period, notable for their technical excellence and the depth with which they convey the personalities of their sitters.

In addition to his sculptural works, Gian Cristoforo Romano was also involved in the design and decoration of several architectural projects, showcasing his versatility as an artist. Despite the abundance of his works, many have been lost or remain unidentified, making the full extent of his contribution to the Renaissance art world somewhat elusive.

Gian Cristoforo Romano's influence extended beyond his immediate contemporaries, contributing to the development of portrait sculpture in Italy and across Europe. His ability to infuse classical ideals with the individual characteristics of his subjects helped bridge the gap between the medieval and modern conceptions of portraiture. He died in 1512, leaving behind a legacy that would inspire future generations of artists to pursue realism and humanism in their work.