Athanasius Kircher Paintings

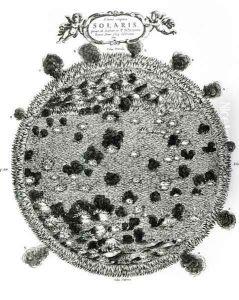

Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who lived during the 17th century, a period often referred to as the Age of Enlightenment. Born on May 2, 1602, in Geisa, in the Holy Roman Empire (now in modern-day Germany), Kircher was a prolific scholar whose interests spanned a wide range of disciplines, including comparative religion, geology, and medicine. However, he is perhaps best known for his work in the fields of Egyptology and the study of hieroglyphs, as well as his contributions to the development of scientific instruments.

Kircher was educated at the Jesuit College in Fulda, where his aptitude for languages and science became apparent. He later joined the Jesuit order and continued his studies in philosophy and theology at Paderborn and Cologne. Kircher's intellectual curiosity led him to pursue research in a variety of subjects, which was evident in his extensive travels throughout Europe. His journey to Malta, Sicily, and other parts of Italy in 1637-1638 played a crucial role in his research on the plague, which he later documented in his work on the subject.

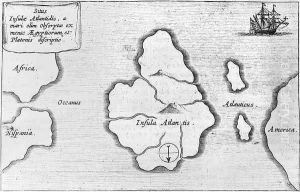

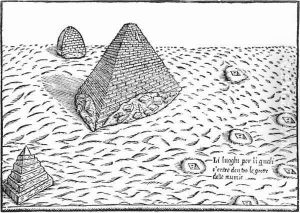

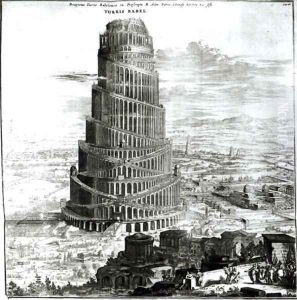

Kircher's most notable contribution to the field of Egyptology was his work 'Oedipus Aegyptiacus' (1652-1654), a comprehensive study of Egyptian culture, language, and history. Although later scholarship would prove many of his interpretations of Egyptian hieroglyphs to be incorrect, Kircher's efforts marked an important step towards the development of Egyptology as a scientific discipline. He was among the first to propose that the ancient Egyptian language was a reflection of their culture and beliefs.

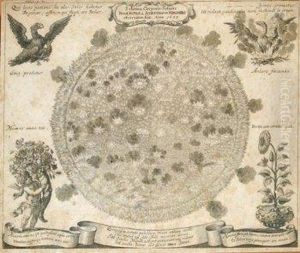

In addition to his Egyptological studies, Kircher made significant contributions to the development of scientific instruments. He invented the 'magic lantern', an early form of the slide projector, and made advancements in the fields of magnetism, optics, and acoustics. Kircher's curiosity also led him to construct one of the first known models of the Earth's core and to propose theories about the spread of diseases, which anticipated later germ theory.

Kircher's work was widely influential during his lifetime, and he corresponded with scientists and scholars throughout Europe. Despite some of his theories being later disproved, his approach to combining empirical research with a broad interdisciplinary perspective has left a lasting legacy in the history of science. Kircher passed away on November 28, 1680, in Rome, leaving behind a vast body of work that reflects the intellectual curiosity and spirit of inquiry that characterized the scientific revolution of the 17th century.