At the end of the 16th century, Rome underwent an unprecedented urban transformation, making it a model for urban design in Europe. This was not only a triumph of architecture and urban planning but also a powerful declaration of the Counter-Reformation Church's influence. During this period, Rome's urban landscape changed dramatically, with the Capitoline Hill being one of the most striking examples.

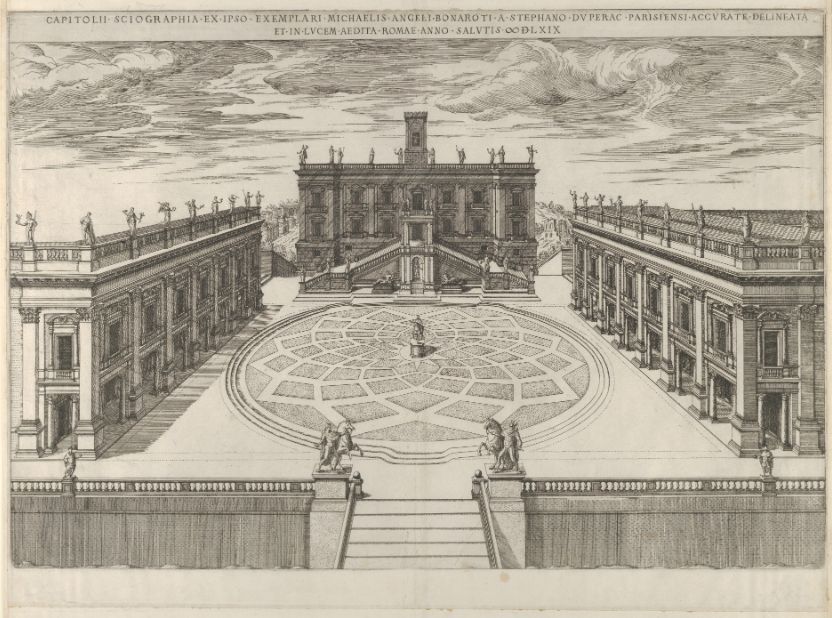

The Capitoline Hill, one of the seven hills of ancient Rome, was the political and religious center during the Roman Empire. In the 16th century, the renowned Renaissance artist Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Paul III to redesign the square. Michelangelo's design ingeniously combined the historical ruins of ancient Rome with the aesthetic principles of the Renaissance, making the Capitoline Hill not only one of Rome's iconic architectural complexes but also a classic case in the history of European urban design.

Michelangelo's design included not only the overall layout of the square but also the facades of the surrounding buildings. At the center of the Capitoline Hill is a beautiful mosaic pavement, surrounded by three significant buildings: the Palazzo Senatorio, the Palazzo dei Conservatori, and the Palazzo Nuovo. Through redesigning the facades, Michelangelo created a harmonious visual unity among these buildings, emphasizing the centrality of the square.

The transformation of Rome during this period was not limited to the Capitoline Hill but extended to the entire city. As the capital of the Christian world, Rome was seen as a great magnet attracting pilgrims from all over the world. In the 4th and 5th centuries, the first churches in Rome were mostly built on the outskirts of the city to accommodate the large number of pilgrims. However, over time, these churches gradually became integral parts of the city. To solve the problems faced by pilgrims entering the city and to create new order out of chaos, Rome's urban planning saw a comprehensive revival.

In the 14th century, Rome's situation worsened significantly with a sharp population decline and urban decay. The Tiber River became the only water source, and the population clustered around its banks. The absence of the Pope and the subsequent church schism left Rome without effective governance, further exacerbating the city's disorder. After Pope Martin V was elected, he ended the period of schism and began the task of rebuilding the city, which had once been home to over a million people during the Roman Empire but had shrunk to a mere 17,000 inhabitants living in dilapidated conditions. He ordered a comprehensive urban development plan, leveraging the vast open spaces within the city walls.

These plans were implemented under the leadership of Pope Nicholas V. Nicholas V possibly received assistance from the famous Renaissance architect Alberti. Alberti, the first theorist of Renaissance urban design, proposed the concept of the city as a planned human environment, an artwork. This notion almost foreshadowed what we now call "urban planning." However, these plans were not fully realized, only relocating the papal residence and government offices from the Lateran Palace to the Vatican.

In the 16th century, Pope Julius II commissioned Bramante to design the city, planning the Via Giulia. This street, the first major thoroughfare built since ancient Rome, connected administrative offices and private residences, creating a unified visual corridor. By the 1530s, this street extended further, linking various pilgrimage churches and unifying the urban districts.

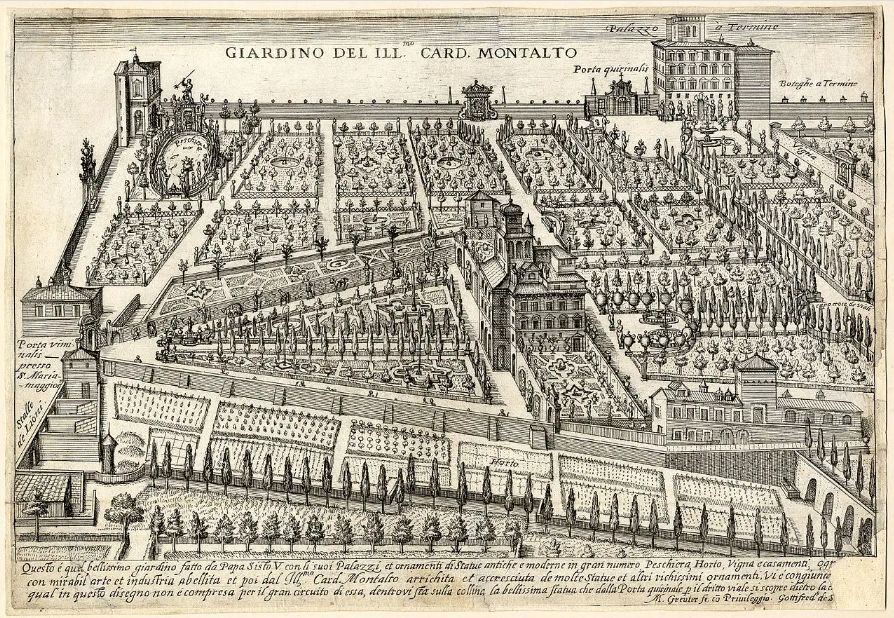

During his papacy, Pope Sixtus V further advanced the city's revival. He erected tall ancient Egyptian obelisks in front of newly formed squares at pilgrimage churches. These obelisks, originally buried in the ruins of the empire, were excavated and crowned with iron crosses. Additionally, he constructed new aqueducts, the first since ancient times, bringing fresh water to the northern parts of the city and promoting urbanization along the riverbanks.

The urban planning of Sixtus V, guided by his chief engineer Fontana, is renowned for its comprehensiveness. In 1590, Fontana wrote, "Sixtus extended streets from one end of the city to the other, unconcerned with crossing hills and valleys, transforming them into gentle plains, creating the most beautiful scenery." This planning integrated all elements of Renaissance urban design within a vast, unified, and visually cohesive environment, addressing practical needs while inspiring religious fervor through visual perspectives.

Rome's urban revival was not just an achievement in architecture and urban planning but also a cultural and spiritual renaissance. The reconstruction of the Capitoline Hill and other significant architectural complexes restored the grandeur of ancient Rome and left a valuable legacy in urban design for future generations. Through the rebuilding of Rome, Renaissance artists and architects demonstrated their creativity and profound understanding of urban aesthetics, providing crucial references and inspiration for modern urban planning.