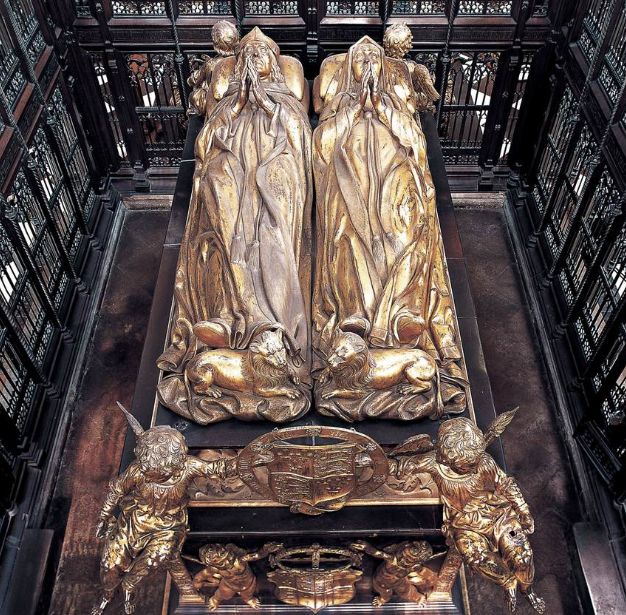

Italian Renaissance art, with its innovative forms, rich themes, and exquisite techniques, quickly spread across the European continent. However, Northern Europe was relatively slow and conservative in adopting these new styles. In the early 16th century, Italian Renaissance art coexisted with the still-active Gothic style in many places, creating a unique artistic landscape. The tomb of Henry VII and his wife is a prime example of this artistic convergence.

Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty, re-established royal authority in England after ending the 30-year civil war. Consequently, his tomb needed to reflect his significant status. Henry VIII recruited the renowned Italian sculptor Pietro Torrigiano (1472-1528) for this purpose. Torrigiano, a classmate of Michelangelo who famously broke Michelangelo's nose during a quarrel, had studied under Giovanni, a disciple of Donatello.

Torrigiano's design for Henry VII's tomb exhibited clear Italian Renaissance influences. The tomb featured nude putti, intricately classical columns surrounding the sarcophagus, Florentine-style angel faces at the corners, and statues of the king and queen that adhered to naturalistic standards. This tomb not only demonstrated the influence of Italian Renaissance style in the north but also highlighted the coexistence of this new style with traditional Gothic elements.

Despite the adoption of Italian Renaissance style in royal memorial buildings in England and France, its widespread acceptance was a gradual process. At Westminster Abbey, the bronze screen surrounding Henry VII's tomb was designed in the distinct English "Perpendicular Gothic" style, complementing the Gothic arches of the church. Even after the tomb was completed, Gothic-style statues of saints filled the church's niches, making them appear as if they belonged to a century earlier.

The "Perpendicular" style was unique to England, originating in the mid-14th century and continuing until the late 16th century. Similarly, in France, Gothic style evolved into the "Flamboyant" style with intricate curved window tracery, persisting into the 16th century. In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, a more robust yet equally ornate Gothic style developed. The city hall of Ghent is a famous example of this Gothic style, with its intricate curves expressing the prosperity of this major trading center.

In these Northern countries, the influence of the Italian Renaissance gradually became evident. For instance, in 1517, Margaret of Austria, the ruler of Belgium, expanded her palace in Mechelen with a purely Renaissance-style addition. Conversely, the city hall of Ghent, completed in 1518, adhered to traditional Gothic style. This stylistic choice reflected the societal tendencies of the time: the wealthy citizens of Ghent preferred the old Gothic style associated with civic freedom, while the rulers favored the new classical style endorsed by the southern monarchies.

This choice of styles not only reflected artistic preferences but also mirrored the social, political, and cultural diversity of the period. The introduction of Italian Renaissance art was not merely an enhancement of artistic forms but a deepening of cultural ideas. Northern Europe, in the process of adopting the Italian Renaissance, retained its traditions while assimilating the new styles, creating a unique artistic synthesis.

The fusion and conflict between Italian Renaissance and Northern Gothic styles were not merely a simple overlay of artistic styles but a profound cultural interaction. Through this interaction, European art in the 16th century reached new heights, maintaining its distinctiveness while mutually influencing each other, collectively advancing the development of European art.