From the 17th to the 19th century, Nature, Imitation, and Invention became central concepts in the formation of academic art. However, these terms had different meanings at the time compared to their modern interpretations. Nature not only referred to the natural world but also symbolized a creative force that artists sought to emulate, especially in the representation of human figures. Imitation was not merely about copying but about understanding and depicting underlying principles. Invention did not refer to originality but to the selection and portrayal of subjective matters, particularly in history painting, which depicted noble and morally elevated actions.

The founders of these ideas, such as Alberti and Bellori, were deeply influenced by classical education and Western philosophy. From Plato's "ideas" to Aristotle's notion that "representation should be what nature intended," they emphasized that art should reflect the ideal forms of nature rather than an accurate replication of reality. For instance, Alberti mentioned in his treatise "On Painting" that the painter's goal is to reproduce objects but must idealize and enhance what is seen. He also noted that great painters like Zeuxis used five models to create a single ideal image.

During the Renaissance and subsequent periods, theorists believed that painting should, like poetry, educate and delight. Horace's phrase "as is painting, so is poetry" highlighted the idea that painting, like poetry, should have a moral uplifting effect, teaching and pleasing the viewer. This perspective was further reinforced during the Renaissance, becoming a cornerstone of art theory at the time.

In his speech "The Idea of the Painter, Sculptor, and Architect," Bellori elaborated on a refined version of Platonism, emphasizing that the artist's ideas should be formed in the mind or imagination, and art should unify the real and the beautiful. He criticized artists like Caravaggio for merely imitating nature's flaws instead of studying nature's common features and the beauty that comes from refinement. In art academies, students were required to draw from life models and to copy famous ancient statues, fostering their understanding and ability to recreate beauty.

Bellori's work "Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors, and Architects" laid the foundation for academic art theory in France and significantly influenced the development of European visual arts. He dedicated this book to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French Prime Minister, whose support for the Paris Royal Academy was crucial. This academic theory continued to dominate European visual arts until the late 18th century and its influence extended into the 19th century.

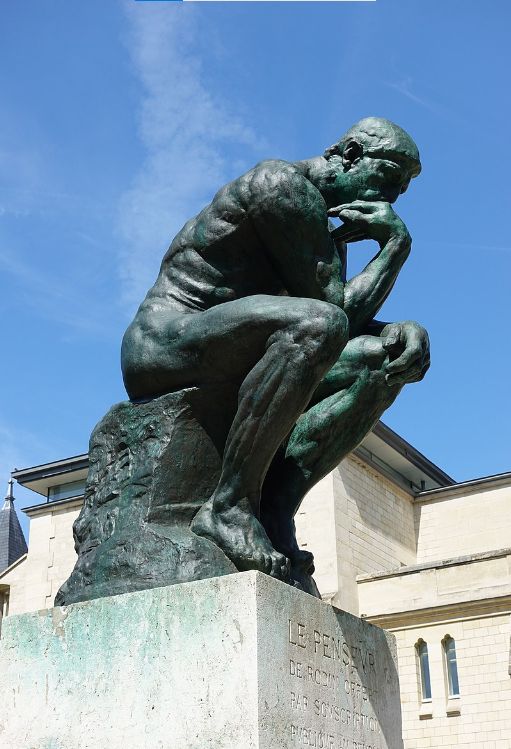

In academic art theory, Nature was seen as a source and standard for creation. Rodin pointed out that ancient art was great because ancient people were the most serious and admirable observers of nature. Artists were encouraged to draw inspiration directly from nature, rather than merely imitating the works of their predecessors. Faure also emphasized that the harmony of art should follow the rules of the universe, a view reflected in both his and Rodin's theories.

Imitation in academic art was not simply about copying but about deeply understanding and reproducing the essence of the subject. Sculptors like Despiau and Maillol embodied this concept in their works, combining initial impressions with detailed analysis to reflect the constructive tendencies of the new world. This imitation was not only evident in artistic forms but also in the profound comprehension and depiction of subjects.

Invention in academic art involved how artists selected and portrayed subjective matters. For example, in history painting, artists not only had to reproduce historical events but also elevate their moral and aesthetic values through artistic techniques. This invention was not just technical innovation but a profound understanding and recreation of the essence of art.

By the mid-16th century in Rome, art academies had developed a systematic method of education. Students were trained to draw from life models and to copy ancient statues, enhancing their understanding and ability to recreate beauty. This educational system improved their technical skills and shaped their understanding and pursuit of art.

Nature, Imitation, and Invention, as core concepts of academic art, played significant roles in art theory and practice from the 17th to the 19th century. By understanding and applying these concepts, artists not only reproduced the beauty of nature but also created unique artistic forms and values through imitation and invention. This period's art theories influenced contemporary artistic creation and laid the foundation for future artistic development. Through the combination of Nature, Imitation, and Invention, academic art reached new heights, providing valuable theoretical and practical experience for the development of art in later centuries.