Bertoldo di Giovanni (c. 1420-1491), a student and assistant of Donatello, and later a teacher of Michelangelo, made significant contributions to Renaissance art through his small-scale works, particularly medals and bronze statuettes. These works encapsulate the Renaissance ideals in a condensed form, serving as a bridge between two of the greatest sculptors of the period.

Medals: Reviving Ancient Roman Art

Bertoldo's medals hark back to the coins of the Roman Empire (medals originally referred to coins that were no longer in circulation). However, these medals represented a rebirth rather than a mere revival of ancient Roman art. Pisanello (Antonio di Puccio Pisano, 1395-1455), an excellent painter and draftsman, was the first artist to specialize in making medals, essentially creating a new art form.

Pisanello's medals typically featured a profile portrait on the obverse side, with more personal characteristics and bold sculptural techniques than the emperor's heads on ancient coins. The reverse side often displayed symbolic designs. For example, the medal of Domenico Malatesta Novello has his portrait on the obverse and a scene of a knight praying before a cross on the reverse, depicted with simple yet profound symbolism. Another medal commemorating the marriage of Leonello d'Este and Maria of Aragon shows Cupid teaching a lion (symbolizing Leonello) to sing. These medals became popular among humanists, serving as a medium to spread personal fame and containing intricate and philosophical designs.

Bronze Statuettes: The Rebirth of Ancient Aesthetics

Bertoldo's bronze statuettes were also highly regarded during the Renaissance. Unlike the medieval religious statuettes, these openly expressed pagan themes. Inspired partly by descriptions from Latin literature, such as the poet Statius' first-century praise of a small Hercules statuette, these works exemplified the rebirth of ancient forms and aesthetic attitudes in 15th-century Italy.

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1433-1498) created a series of bronze sculptures like "Hercules and Antaeus," where the rebirth encompassed not only the ancient forms but also an ancient attitude towards beauty. Pollaiuolo's bronze statuette depicts the dynamic tension of male nudity in motion. The sculpture is designed to be held and turned, appreciated from multiple viewpoints, capturing the dramatic and physical energy in a concentrated form. For the original owner, likely Lorenzo de' Medici, the sculpture also held significant symbolic meaning, portraying Hercules as a Renaissance man, an immortal mortal achieving greatness through his efforts. The story of Hercules overcoming Antaeus (who was invincible as long as he touched the ground) adds a deeper philosophical layer to the work.

Antico's Art: Pure Aesthetic Pleasure

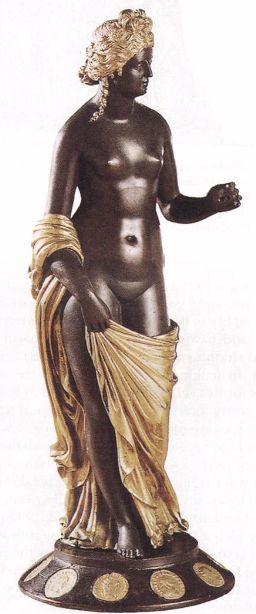

Antico (Piero Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, died 1528) represented another style in the bronze statuette tradition. His works, such as "Venus Felix," are examples of pure aesthetic pleasure, showcasing exquisite artistry without deeper symbolic meanings. These pieces were cherished in private collections during the Renaissance for their delicate craftsmanship and hedonistic beauty.

These medals and bronze statuettes not only embodied the ideals of Renaissance art but also served as perfect mediums for artists to convey grand philosophical and aesthetic thoughts through small-scale works. The works of Bertoldo, Pisanello, and Pollaiuolo highlight how Renaissance artists revived and transformed ancient forms and attitudes to express profound human ideals and beliefs. These artworks were not only popular in their time but also left a lasting cultural legacy for future generations.