The term "Mannerism" originates from the Italian word "maniera," which was commonly used in the 16th century to describe social behavior and art. It not only represented style or manners but also encompassed novelty, grace, aesthetic taste, fluidity, and refinement. These characteristics were often seen in the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. However, there is a distinction between "manner" and "mannered," with the latter referring to the imitation of someone else's distinctive style or the conscious display of personal traits.

In the mid to late 16th century, the term Mannerism took on a pejorative meaning, describing artists who used harsh colors and depicted figures in twisted, unnatural perspectives. Mannerists were seen as a reaction to or continuation of High Renaissance ideals, with numerous conflicting definitions and interpretations. This style was considered a reflection of 16th-century aesthetic theory, emphasizing the intricacies and expression of art itself.

The formation of Mannerism was closely linked to the social upheavals in 16th-century Europe. The Reformation, political unrest, and the discovery of the New World significantly influenced the art of this period. Artists, through complex compositions and rich details, sought to express their inner anxieties and unease.

Mannerism emerged in mid-16th century Italy, during a time of significant social change brought about by the Reformation. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) marked the Catholic Church's official response to Protestant reform. This council not only influenced religion but also had a profound impact on art. It emphasized the moral and didactic functions of religious art, prompting many artists to seek new modes of expression to meet the church's new standards.

In this context, Florence and Rome in northern Italy became the main hubs of Mannerism. Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, and Rome, the center of the Catholic Church, played crucial roles. Mannerism flourished in these cities and quickly spread to other regions of Italy and Europe.

Jacopo Tintoretto was one of the key figures of Mannerism, known for his dramatic contrasts of light and dynamic compositions. His masterpiece "The Last Supper" showcases his unique techniques in composition and lighting. The scene is filled with movement and drama, with exaggerated poses and bold perspectives creating a strong visual impact.

Another significant Mannerist artist was Parmigianino. His work "Madonna with the Long Neck" is famous for its asymmetric composition and the exaggerated proportions of the figures. The elongated neck and elegant yet strange posture of the Madonna highlight Mannerism's challenge to and departure from traditional aesthetics.

Mannerism was not limited to painting and sculpture; it also influenced architecture and decorative arts. Giulio Romano was a key figure in Mannerist architecture. His design for the Palazzo del Te in Mantua is renowned for its peculiar decorations and bold architectural forms. Romano used numerous decorative elements in his architecture, breaking away from traditional symmetry and proportions to create a strong visual effect.

Mannerism's influence extended beyond Italy. Artists in France, Spain, and the Netherlands drew inspiration from it, creating distinctive styles of their own. For example, the Fontainebleau School in France was heavily influenced by Italian Mannerism, known for its intricate decorations and elegant style.

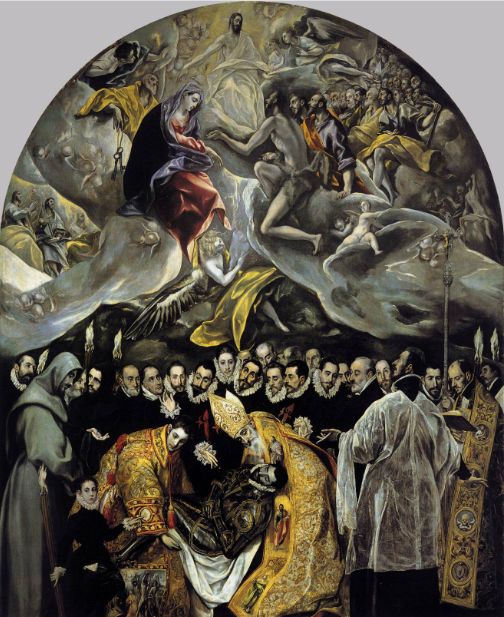

In Spain, Mannerism blended with the local religious atmosphere to form a unique style. El Greco, a prominent figure in Spanish Mannerism, was known for his rich colors and distorted forms. His painting "The Burial of the Count of Orgaz" exemplifies typical Mannerist traits with elongated figures, vivid colors, and strong contrasts.

Dutch Mannerism was more evident in painting and decorative arts. Hendrick Goltzius was a notable Dutch Mannerist, famous for his intricate lines and detailed depictions in his prints. His works reflect Mannerism's focus on detail and decoration while showcasing the artist's innovations in composition and form.

Mannerism's influence continued into the 17th century, significantly impacting Baroque art. Baroque art inherited the drama and dynamism of Mannerism but placed greater emphasis on emotional expression and audience engagement. Baroque masters such as Bernini and Caravaggio further developed Mannerism's visual effects, creating more compelling and immersive artworks.

A distinctive feature of Mannerism is the pursuit of ideal beauty and the distortion of reality. Artists used exaggeration and transformation to create dramatic and tension-filled images. Mannerist works often broke traditional symmetry and proportions, aiming for an unsettling and dynamic aesthetic. This aesthetic reflected the artists' contemplation of reality and expression of inner emotions.

Another characteristic of Mannerism is the focus on complex details. Artists employed numerous decorative elements, filling their works with details and variations, providing viewers with a rich visual experience. This complexity in detail not only demonstrated the artists' skills but also their dedication to the pursuit of beauty.

Although Mannerism was not widely recognized in its time, it had a profound impact on subsequent artistic developments. It laid the foundation for the emergence of Baroque art and provided insights for the development of modern art. Many modern artists draw inspiration from Mannerism, continuing to explore and perpetuate its artistic spirit through the reinterpretation and innovation of traditional styles.