In the history of fifteenth-century Italian architecture, the Palazzo Medici is undoubtedly a significant milestone, especially influencing the architectural style of Florence. The design of Palazzo Medici was not just to display power and wealth, but to convey a sense of solemn and simple aesthetics through its clean and orderly design.

The exterior of the Palazzo Medici is characterized by its simple window layout and the meticulous adjustment of materials. The ground floor uses heavy stone blocks, giving a sense of stability and solidity. The second floor employs rustication, adding depth and texture to the building. The top floor features a flat wall, shaded by substantial eaves, which are not only aesthetically pleasing but also practical for shading.

However, the interior courtyard of the Palazzo Medici presents a different aspect. Composite columns support arches, forming an elegant and simple space. Circular reliefs surround the courtyard, enhancing the artistic and decorative nature of the building. This design not only reflects the Medici family's love for art but also shows their high regard for detail and aesthetics.

In contrast, Jacques Coeur's mansion, built around the same period in France, appears more complex and varied. Coeur's mansion seems to have grown organically, with rooms of different shapes added horizontally or vertically based on function or whim. Decoratively, this mansion adopts a more elaborate Gothic style, featuring whimsical decorations such as figures peering out of simulated windows and carvings hinting at the owner's name. This style forms a stark contrast with the simplicity and solemnity of the Palazzo Medici.

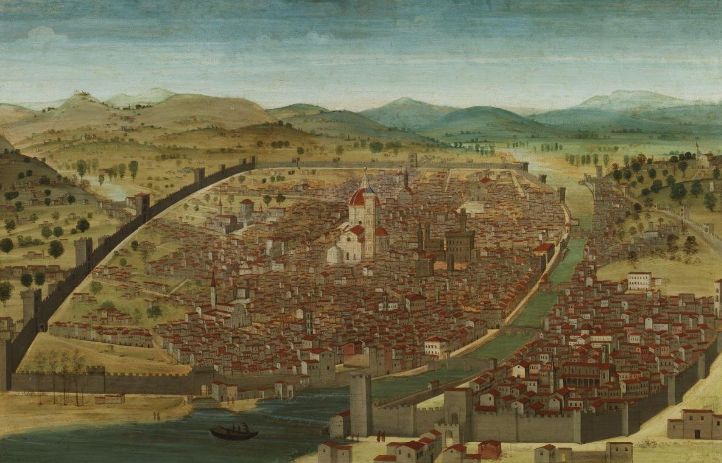

The owners of these buildings were clearly the decision-makers of their designs. Jacques Coeur's residence gives an impression of wealth and luxury, whereas Cosimo de’ Medici’s residence exhibits ample and stable wealth. As the head of the Medici bank and the wealthiest man in Florence, Cosimo was the foremost citizen of the Florentine Republic and took his civic responsibilities seriously. His residence served as his home and an ornament that added splendor to the city, a "suitable" model that implied more than just good taste. It is said that he rejected a design by Brunelleschi for being too luxurious and ostentatious, opting instead for Michelozzo di Bartolommeo, whose art and life adhered to the principles of prudence and frugality, earning Cosimo’s favor.

Michelozzo’s design style indeed reflected Cosimo’s prudence and frugality. This architect was not just designing buildings but was conveying a lifestyle and philosophy. This design philosophy is evident in every detail of the Palazzo Medici, from the austere exterior to the elegant and harmonious interior courtyard, showcasing a restrained and profound aesthetic.

Besides the Palazzo Medici, Leon Battista Alberti is another important figure in the history of Italian architecture. Alberti was not only an architect but also an ethicist, lawyer, poet, playwright, musician, mathematician, scientist, painter, sculptor, and aesthetic theorist. In his writings, Alberti developed a rational theory of beauty based on ancient practices and what he called “natural laws.” His development had a significant impact on fifteenth-century Florentine architecture, fundamentally transforming the role of architects.

Alberti’s design style was heavier in form and more archaeologically accurate than Brunelleschi’s. He used columns primarily for decoration rather than structural functions, and these columns always combined with entablatures rather than arches. His greatest achievement was applying the elements of classical columnar temples (where walls were seen as mere infill between upright supports) to the design of wall openings. Another innovation was his professionalization: he focused solely on design rather than construction.

One of Alberti's representative works is the San Francesco in Rimini, also known as the Tempio Malatestiano. Alberti designed a marble shell for this old church, using the Roman triumphal arch on the façade to symbolize victory over death, with deeply carved arched niches on the side walls housing simple sarcophagi dedicated to poets and philosophers. This building had no Romanesque revival elements; everything was grandly Roman, showcasing Alberti’s mastery of classical architectural language.

The construction of Duke Federigo da Montefeltro’s palace in Urbino also reflects the unique style of Italian architecture in this period. This extensive building emphasized subtle proportional adjustments and intricate sculptural decorations, even more refined than the earlier Palazzo Medici. The study and loggia in the palace were not meant for public display but for the Duke’s personal pleasure, embodying the achievements of early Renaissance humanism.

Through these architectural works, we can clearly see the unique development of Italian architecture in the fifteenth century. Whether it is the austere grandeur of the Palazzo Medici or the rational aesthetics of Alberti, each detail demonstrates the excellence of Italian architects in combining aesthetics and functionality. These buildings are not just historical monuments but perfect combinations of art and philosophy, leaving a precious cultural heritage for future generations.