In the 15th century, whether in Italy or Northern Europe, the majority of visual arts remained religious. Although portraits were on the rise and no longer limited to members of ruling families, they were still scarce compared to religious depictions like "Madonna and Child." Mythological scenes were also quite rare and were typically imbued with moral significance, if not explicitly religious meaning. Records from the Tuscan region before 1550 mention 500 or more religious paintings and sculptures, compared to fewer than 40 secular paintings.

In 15th-century Florence, artists began focusing on the demonstration of their skills, a trend likely influenced in part by economic conditions. Economic historians note that the 15th century was not a period of economic expansion but rather a slow and incomplete recovery following the Great Depression of the mid-14th century. This led some merchants and bankers, finding trade unprofitable and agriculture unviable, to invest in culture, thereby attributing nominal value to these cultural investments. Consequently, Florentine art, particularly architecture, exhibited a tendency toward simplicity and moderation.

The shortage of materials also impacted the style and form of art. By the mid-15th century, the shortage of precious metals like gold and silver prompted artists to shift their focus from the value of materials to the skill of the artist. This phenomenon is exemplified by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, who abandoned a successful career as a goldsmith to pursue painting, foreseeing that painting would bring more lasting fame than goldsmithing.

In the late 15th century, secular paintings began to increase, and many large private residences and summer villas were built in and around Florence. Nonetheless, religious themes still dominated. However, due to the shortage of materials, artists gradually turned to more economical materials. For example, painted ceramics, as perfect as enameled gold vessels, and small wooden chests adorned with artificial gems, were crafted from modest materials but designed and decorated with great skill and artistry.

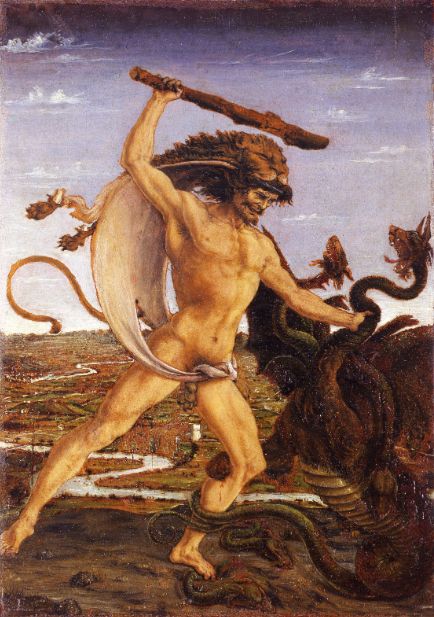

The cassoni (chests) of the 15th century were often decorated with the family crests of the bride's and groom's families, reflecting the importance of marriage in forging political and commercial alliances. These cassoni were sometimes very elaborate, combining vibrant and lively scenes painted on panels. While most panels depicted scenes from ancient history or mythology, some of the most popular themes included the abduction of the Sabine women by Romulus and his companions.

After these chests were dismantled, many painted panels were preserved as independent paintings. These paintings maintained the tradition of International Gothic art until the mid-15th century when scenes crowded with various events and figures began to appear. The clothing and postures of the characters in these paintings matched contemporary fashion, demonstrating a courtly atmosphere. Even though Florentines were city dwellers, merchants, and nominally supporters of the republican system, they still harbored an apparent admiration for the ideals of feudal knighthood.

In conclusion, during the 15th century, European art, particularly secular painting in Florence, began to emerge amidst the dominance of religious themes. Despite economic and material constraints, artists continuously explored and showcased their skills and creativity in the new social and cultural environment, making secular painting increasingly distinct and appealing during this period.