During the golden age of Venice, the "Scuole Grandi" (Great Schools) and "Scuole Piccoli" (Small Schools) were two prominent social and religious phenomena. The Scuole Grandi were major religious organizations formed by laypeople, while the Scuole Piccoli were smaller and more numerous groups. Their existence not only reflected the religious atmosphere of the time but also highlighted the critical role of art patronage in this context.

The Scuole Grandi were among the five main lay religious groups in the Venice area, established by lay believers in the 13th century. Members of these groups publicly practiced self-flagellation during festivals, attempting to atone for humanity's sins by reenacting the Passion of Christ. These associations included members from various social classes, such as nobility, citizens, and laborers. In Venice's strict oligarchic system, these associations were the only places where members of different social strata could theoretically stand on equal footing.

By the late 15th century, the number of Scuole Piccoli had exceeded 200. These groups were generally established outside church institutions, with most accepting women as formal members and evolving into mutual aid societies that cared for the elderly, weak, poor, and sick. Some small schools engaged in broader charitable work, establishing orphanages and homes for the elderly. Today, similar lay groups, particularly the Misericordia, continue to provide ambulance and emergency services across Italy.

The Scuole Grandi and Scuole Piccoli played unique roles in Venice's social structure. The government viewed these associations as moral guardians but also implemented measures to prevent them from becoming bases for noble political ambitions or centers for public disorder. For instance, regulations stipulated that elected managers had to be citizens, excluding nobles and the lower classes. In 1482, members of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista included not only nobles but also citizens such as ship owners and silk and gold merchants, as well as lower-class individuals like booksellers, fishermen, fruit vendors, and barbers. All members swore to uphold high standards of conduct, and notorious offenders would be expelled.

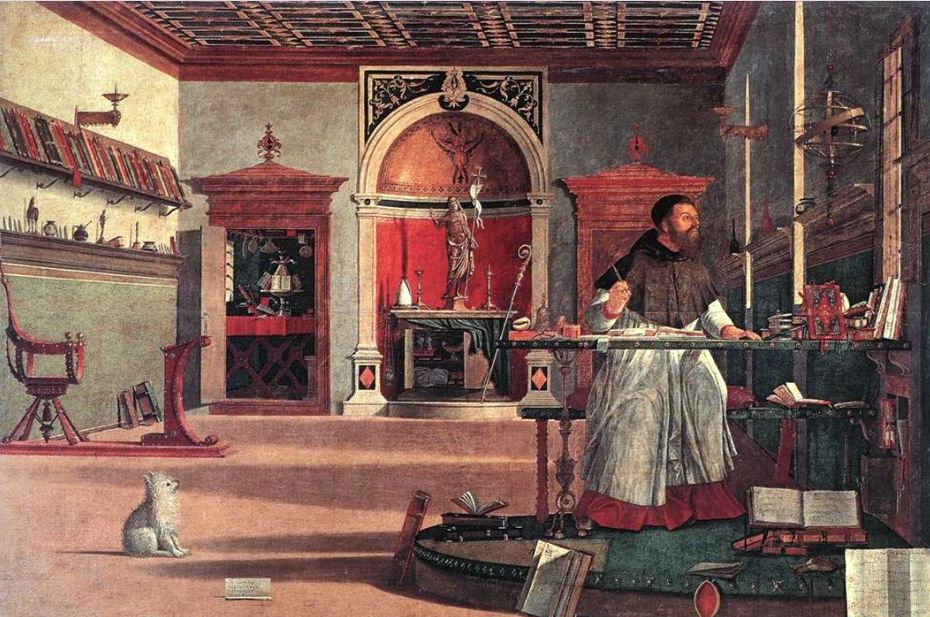

The associations' wealth, often derived from bequests, enabled them to build and decorate grand meeting halls. Managers favored narrative paintings and commissioned artists like Gentile Bellini and Vittore Carpaccio to create these works. The notable aspect of these commissions was not only the artworks themselves but also the unusual manner of patronage. Managers selected the artists, chose the themes, and appointed committees to oversee the work.

Carpaccio created complete narrative series for several associations, although only those made for the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni still survive in their original building. The motivations behind such patronage included piety, similar to acts of charity or lighting candles before altars. However, there might also have been an intention to use these narrative paintings as "eyewitness accounts" of Venetian life, validating the authenticity of miracles and other religious events. These artworks mediated between daily reality and life, aligning with the wishes of the Venetian citizen managers.

While narrative paintings depicted Venice's social structure and material appearance, they were not meant to reflect life accurately. They intentionally concealed underlying conflicts and tensions to present an image of a peaceful and prosperous society. These artworks represented an ideal of a mercantile government, a vision conceived by the wealthy citizen patrons who commissioned them.

These paintings provided not only visual entertainment but also mediated the ambiguities and contradictions of daily life, offering coherence and moral significance to the mundane. The narrative series by Bellini and Carpaccio likely served a similar role, helping viewers understand and accept the complexities of real life through the stories depicted.

Through art patronage, Venice's religious groups enriched the city's cultural atmosphere and played a significant social role. Art allowed members of different social strata to find common ground, creating a unique social harmony. This harmony was not only a visual delight but also a profound understanding and mediation of real life. By appreciating these narrative paintings, we can feel the beauty of art and grasp its far-reaching impact on society.