Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), the Florentine painter, architect, and biographer of artists, vividly depicted the splendid artistic landscape of the Renaissance era with his detailed narratives and meticulous descriptions. Vasari not only demonstrated unparalleled talent in his own creations but also preserved the lives and works of many artists for posterity through his renowned work, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Among these artists, Leonardo da Vinci undoubtedly shines the brightest.

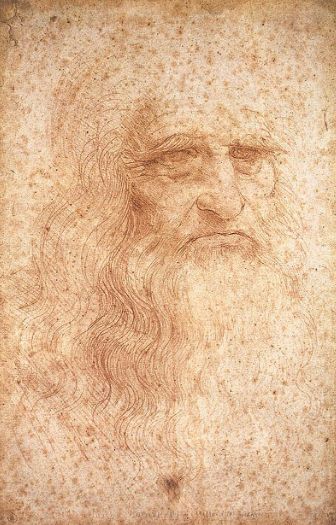

When Vasari looked back at the artistic development of the mid-16th century, he described how, under the leadership of Leonardo da Vinci, art’s "rebirth" transitioned into what he called the "modern" style. This shift was not just a technical innovation but a revolution in artistic concepts. Vasari highly praised Leonardo’s "bold design, meticulous imitation of all natural details, good rules, better order, correct proportions, and divine grace", hailing him as a true genius.

Leonardo’s exalted status stemmed not only from the exceptional quality of his few completed works but also from his endless exploration of art and science. His early work, The Adoration of the Magi (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), although unfinished, showcased his extraordinary compositional skills. Similarly, the war mural for the Palazzo Vecchio remained incomplete, but the sketches and drafts revealed his keen grasp of dynamics and detail.

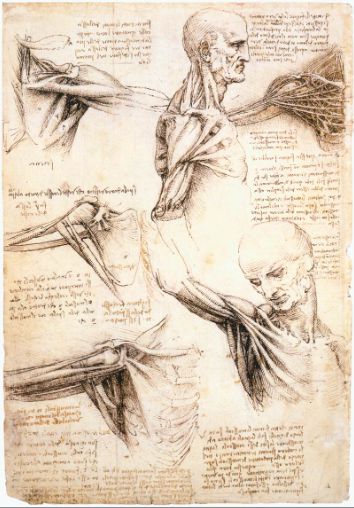

Despite many uncompleted projects, Leonardo's notebooks and sketches in art, science, anatomy, and engineering have become invaluable treasures for future generations. None of his architectural designs were realized, and sculptures like the equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza in Milan were left unfinished. Nevertheless, these did not diminish his greatness. His thousands of pages of notes included rich art theories, anatomical studies, natural history, ornithology, water resource management, and numerous mechanical inventions, all testament to his relentless pursuit of knowledge and art.

Leonardo’s creative philosophy reflected his unique understanding of art and craft. He believed, "The less a man works, the more he will accomplish, because he seeks concepts by means of knowledge and shapes these perfect ideas, afterwards merely putting them into practice with his hands." This concept emphasized the intellectual activity in artistic creation, positing that art is superior to craft, and the artist’s thought and conception determine the final form of the work.

Growing up among humanists in Florence, Leonardo showed little interest in classical scholarship or Neoplatonism. Although he did not learn Latin until he was 40, this did not hinder his independent thinking in art and science. He transcended medieval thought patterns and showed little interest in classical traditions, making him a truly independent thinker.

Leonardo trained in Verrocchio’s workshop, but his interests quickly expanded to encompass all human sciences and natural phenomena. His curiosity and thirst for knowledge focused on what Aristotle called "entelechy", the realization of potential. This made him concentrate on the initial states of nature and art, such as the structural organization of the body before maturity or a painting taking shape but not yet completed. His passion for understanding the human body led him to dissect corpses and create the first accurate anatomical drawings. These not only held scientific value but also provided precise anatomical knowledge for his artistic creations.

Leonardo’s critique of contemporary science also showed his emphasis on experience and practice. He believed that science should be based on experience and that knowledge and conclusions should be derived through sensory experience. He wrote, "In my view, those sciences are both useless and full of errors, as they are not born of experience, the mother of all certainty, and do not end in experience, that is, do not pass through our senses." This view aligned with his practice in art creation, filling his works with realism and vitality.

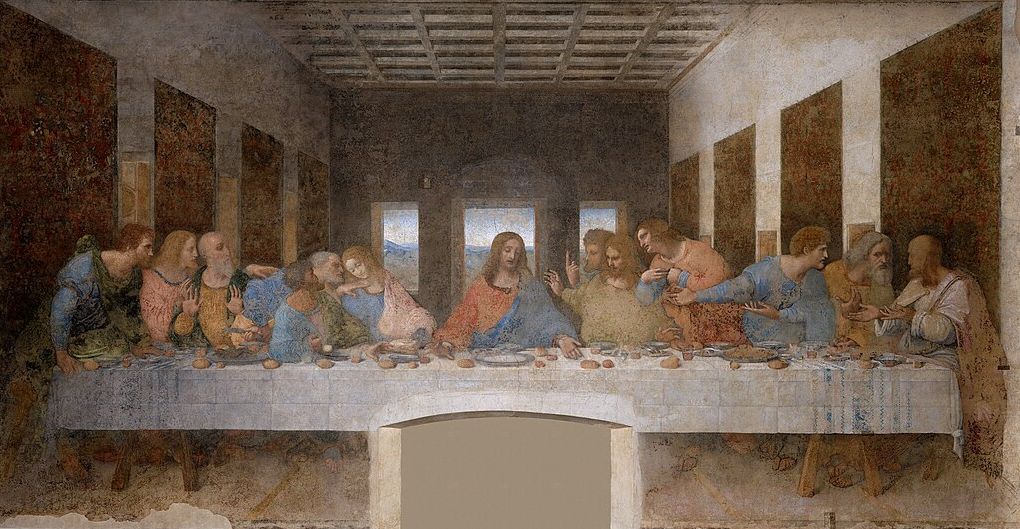

Leonardo’s innovative genius was fully expressed in The Last Supper. This painting broke traditional composition conventions and depicted profound psychology and emotions through the expressions and gestures of the characters. He chose the moment when the disciples asked Christ, "Lord, is it I?" and illustrated each disciple’s unique reaction, creating a network of forms and emotions. This approach discarded the trivial details favored by early 15th-century painters, focusing instead on the inner portrayal of the characters.

Leonardo’s meticulous studies of plants, anatomy, and biological principles of growth allowed him to compose works based on similar systems. In The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, he combined three figures into a pyramid shape, with each form naturally extending like plant stems and leaves. This painting not only showcased Leonardo’s painting skills but also elevated European painting through techniques such as chiaroscuro (light and dark contrast), sfumato (soft blending of colors), and atmospheric perspective, enhancing the sense of volume and distance and creating a mysterious, transcendent atmosphere.

Mona Lisa is undoubtedly Leonardo’s most famous work, recognized for its blurred background and enigmatic smile. Through its hazy tones and ambiguous expressions, Leonardo imbued Mona Lisa with a timeless allure, making it an immortal classic in art history.

Vasari’s praise of Leonardo extended beyond his artistic achievements to his definition of an artist. He considered Leonardo the epitome of a "genius", a status that set him apart among Renaissance artists. Leonardo achieved great success in painting and demonstrated the perfect union of art and science through his research in anatomy and engineering.

Leonardo’s art reflects not only his personal talent and effort but also the Renaissance pursuit of knowledge and beauty. Through Vasari’s accounts, we glimpse this great artist’s journey and creative process, feeling his endless passion for art and science. Leonardo’s legacy is not just a series of masterpieces but a spirit of striving for excellence and continuous exploration, inspiring generations of artists and scientists to pursue truth and beauty.