The Renaissance was a time of great transformation and creativity, where artists found a unique balance between Christian faith and humanism. Though these two might seem opposed on the surface, they were actually intertwined during the Renaissance, jointly fostering the era’s artistic and cultural flourishing.

Humanism emphasized the importance of human dignity and the appreciation of the material world's beauty, a concept that was fully embodied in sculpture. For instance, Desiderio da Settignano's memorial for the classical scholar Carlo Marsuppini exemplifies this philosophy. Carlo Marsuppini, who translated Homer's epics into Italian verse and served as the chancellor of Florence from 1444 until his death, is depicted lying on his tomb with a book in his hands, echoing his funeral scene. The tomb features no overt Christian symbols, instead celebrating Marsuppini’s wisdom and scholarship with a Latin inscription, reflecting humanism’s focus on individual achievement.

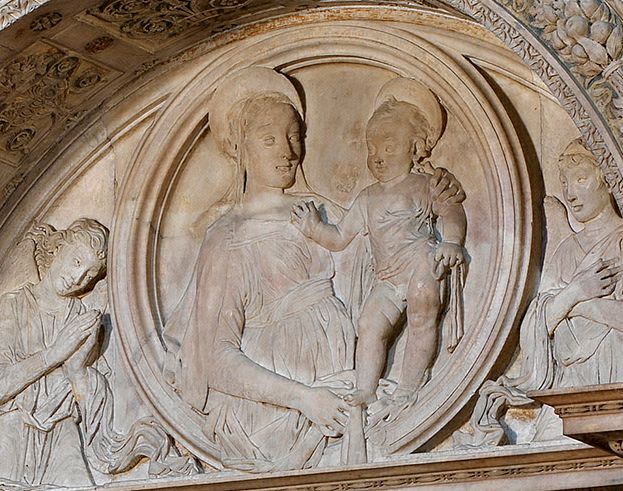

Despite the spread of humanism during the Renaissance, Christian faith remained a significant theme in art. In Marsuppini's tomb, a bas-relief of the Madonna and Child, flanked by angels, adorns the top. These religious elements coexisted harmoniously with the humanist decoration, visually separating yet spiritually integrating Christian faith and humanism.

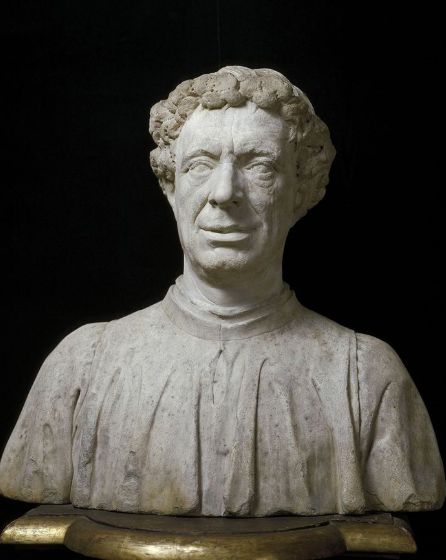

Renaissance artists began to pay more attention to individual characteristics and personality. Settignano’s sculpture of Marsuppini, with its high forehead and prominent cheekbones, broke away from the medieval stylized tomb figures, highlighting personal traits. Settignano, the first Florentine sculptor since ancient Rome to create portrait busts, drew inspiration from ancient ideas rather than forms.

Settignano's contemporaries, such as Antonio and Bernardo Rossellino, also infused humanist thought into their sculptures. Their numerous portrait busts captured personal emotions and unique characteristics, moving away from the rigid styles of the Middle Ages. For example, Antonio Rossellino’s bust of Matteo Palmieri is renowned for its detailed realism and lifelike portrayal.

Renaissance sculptors continuously innovated to achieve more realistic and vivid effects. Andrea del Verrocchio’s "Madonna and Child" bas-relief, for example, exhibited not only exceptional craftsmanship but also employed painted terracotta to impart warmth and bold form to the piece. This technological innovation made art more accessible to the public by providing affordable alternatives to marble and bronze.

Verrocchio was also renowned for training a generation of eminent artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, who learned painting, sculpture, and engineering in his workshop, later integrating these skills into his works.

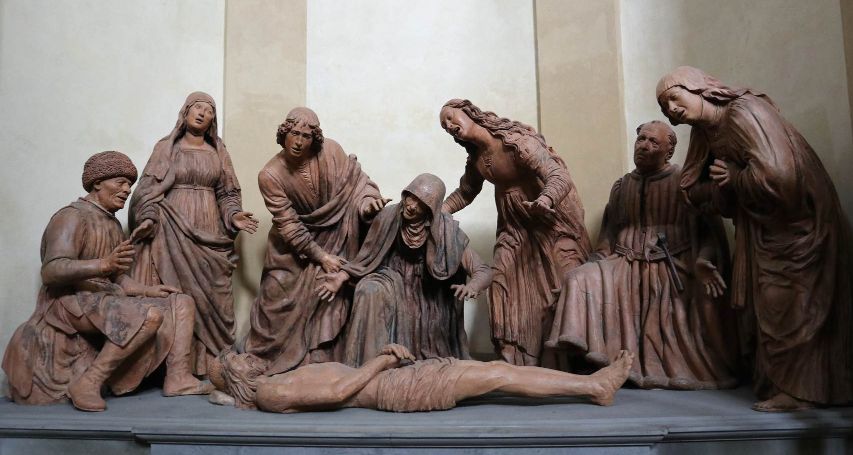

Beyond Florence, many Italian sculptors of the Renaissance adopted an illusionistic style. Guido Mazzoni of Modena, one of the first and most talented sculptors, created life-size, highly realistic statues often depicting scenes from the Gospels, such as the Nativity and the Lamentation. Mazzoni’s works embodied extreme naturalism, enhancing the emotional impact of religious narratives.

Another renowned sculptor was Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose works like "David" and the "Pietà" represented the pinnacle of Renaissance sculpture. "David," a marble statue standing 5.17 meters tall and created between 1501 and 1504, captures the moment before David's battle, showcasing the beauty and strength of the human form. Michelangelo's "Pietà" portrays the Virgin Mary holding the dead Christ, filled with profound emotion and detailed craftsmanship.

Renaissance sculpture celebrated human nature and realistically depicted the world, inheriting the essence of classical art while driving innovation. In these sculptures, the intertwining of Christian faith and humanism can be seen, creating a rich and complex cultural landscape that laid a solid foundation for future artistic development.