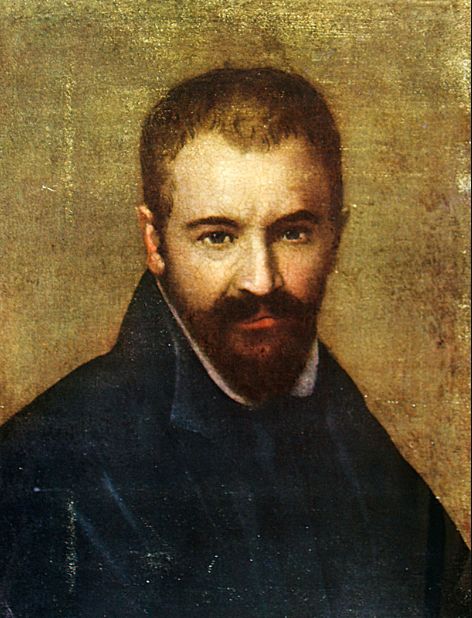

Correggio (Antonio Allegri Correggio, c. 1489-1534) was a prominent painter of the Italian Renaissance, renowned for his unique artistic style and exceptional technique. His development was influenced by the works of Mantegna, Leonardo da Vinci, and their northern followers, forming his own elegant and gentle personal style. Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, Raphael's Stanze di Raffaello, and Titian's "Assumption of the Virgin" profoundly impacted him, although he might have known these works only through pictures.

One of Correggio's most representative works is the dome fresco "Assumption of the Virgin" in Parma Cathedral. This piece broke the limitations of traditional architectural structures, creating a new type of ceiling painting. The painting depicts figures spiraling into heaven, with the viewer seemingly drawn into the scene as part of the grand spectacle. Correggio employed the technique of "di sotto in su" (from below upwards), portraying the elegant bodies of the figures in mid-air, setting new standards for illusionism. This technique not only has a strong visual impact but also gives the viewer a sense of being in the midst of the scene.

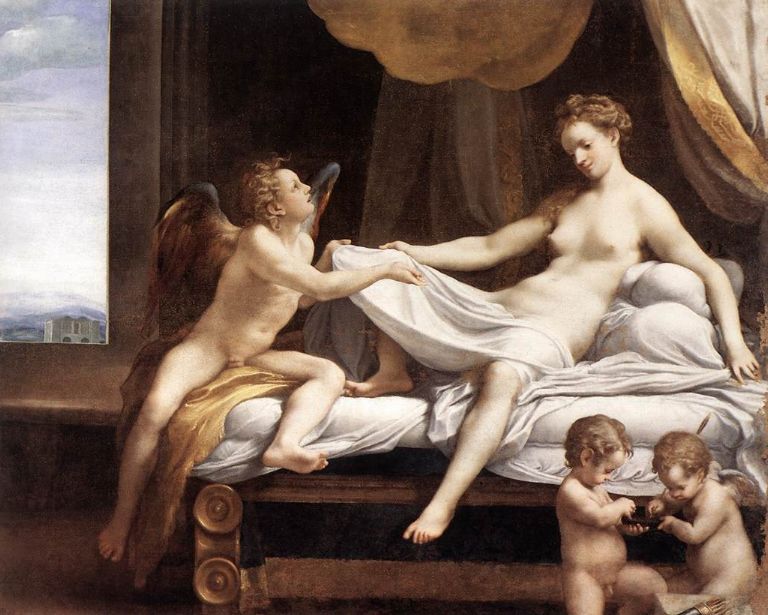

Correggio's oil paintings also excelled, particularly in his delicate rendering of skin. Whether in the dignified saints of his sacred works or the graceful Olympian gods, he demonstrated a masterful handling of the human body. In "Danaë," Correggio depicted the myth of Jupiter descending as a shower of gold to seduce Danaë. Although this theme often carries seductive undertones, in Correggio's rendition, it exudes purity and beauty. Danaë's passive acceptance, combined with her gentle and graceful demeanor, suppresses any sense of licentiousness, creating a scene filled with harmony and rhythm.

Correggio made significant contributions not only in religious frescoes but also in mythological subjects. His paintings "Jupiter and Io" and "The Abduction of Ganymede" vividly bring mythological stories to life, showcasing his exceptional control over expressions and movement. Particularly in handling light and texture, Correggio displayed extraordinary skill, making the mythological figures lifelike and full of dramatic tension and visual impact.

In "Assumption of the Virgin" in Parma Cathedral, Correggio created a work as significant as those of his predecessors. This painting represented a new type of ceiling fresco that completely broke the architectural structure, depicting figures spiraling into heaven, as if the viewer was also drawn into the vortex. Unlike witnessing an event through a stage arch, as in Titian's "Assumption of the Virgin," viewers become part of the scene. Correggio used the "di sotto in su" technique to depict figures from below, showing their graceful limbs in the air, setting new standards for illusionism.

His mastery in handling the human body—no artist could paint the perfect blush on youthful skin more delicately—was fully realized in his oil paintings, whether in the dignified saints or the graceful Olympian gods. In one painting, Danaë's father locked her in a tower to preserve her chastity, but the view outside the window tells us that Jupiter is about to descend in a shower of gold. This theme is often seen as dangerously seductive, but Correggio purified the sensory desires within it. Danaë's passive acceptance, combined with her gentle and graceful demeanor, suppresses any sense of licentiousness. Cupid gently lifts the fabric on her leg, and their bodies form a rhythmic harmony in the composition, creating a light and soft sense of movement.

Correggio's paintings fully expressed the novel concepts of the early 16th century, with his idealized images of youthful beauty never exceeding the bounds of nature. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola Parmigianino, 1503-1540) took this further, pushing elegance and grace to extremes, as seen in his "Madonna with the Long Neck." His inspiration came largely from Correggio, possibly having been his apprentice, and also from Raphael's late works like "The Transfiguration." However, his ideal of feminine beauty seemed derived from literary metaphors rather than art or nature, likening a woman's neck and shoulders to a perfectly shaped vase (hence the long-legged angel on the left holding a vase). Not only the neck of the Madonna but also her hands, right foot, and the limbs of Christ are elongated, elevated to a non-earthly elegance. Below, outside the spatial perspective, a small figure, possibly St. Jerome, unfurls a scroll, adding a slightly unsettling visual feature to the otherwise secular atmosphere of the painting.

This deliberate distortion of the human body in painting has its counterpart in the transformation and addition to classical order in architecture. Michelangelo's Medici Chapel set a precedent, and in the Laurentian Library vestibule connected to the same church, he was bolder. Vasari noted that all architects should thank Michelangelo for "breaking the chains of tradition." Around the same time, Raphael's former pupil and assistant Giulio Romano also enjoyed the same "license"—a term representing recognition in the 16th century. In 1526, he began work on the Palazzo Te just outside Mantua. For this rural structure, he used Doric order and covered the walls from base to top with brickwork. However, the spacing of the half-columns was most irregular, with triple-garlanded decorations inexplicably sliding down from the originally correct entablature between each column. In the provided image, the windows beside the courtyard have no frames and push directly to the top of the wall, squeezed between the narrowly spaced columns. The prominent position is thus given to the niches under the windows and the closed windows crowned with a conspicuous pediment in the wider spaces. These contradictions are quite confusing, but Romano's purpose seemed not to shock but to please those knowledgeable in architectural theory, who could appreciate the ingenuity. The effect of these contradictions is akin to the rhetorical oxymoron, such as in Aretino's letter to Romano: "always a modern sense of antiquity, and an antiquity in modernity."

Correggio's art did not just stop at forming personal style and technical innovation; more importantly, it lay in his deep understanding and perfect fusion of religious and secular art. His works infused religious art with rich humanistic sentiment and reflected a profound insight into the beauty of human nature in secular art. This artistic philosophy endowed his works with high artistic value and influence both in his time and later generations.

Throughout his painting career, Correggio continuously explored and innovated, eventually forming a unique artistic style. His ideal of human beauty never exceeded the bounds of nature, allowing his works to maintain a harmonious naturalism while being delicate in their depiction. This is fully evident in both his frescoes and oil paintings.

In summary, Correggio's artistic achievements lie not only in the creation of an elegant and gentle painting style but also in his profound understanding and unique expression of art's essence. His works are not only representative of the artistic accomplishments of the Renaissance but also treasures in the history of human art. Whether in grand religious pieces like "Assumption of the Virgin" or mythological masterpieces like "Danaë," Correggio, through his art, showcased an era's infinite pursuit and deep understanding of beauty and harmony.