The Renaissance marked a significant turning point in European history, symbolizing the transition from the Middle Ages to modern civilization. This period brought profound changes not only in art and culture but also in science, philosophy, and various social fields. The Pazzi Chapel in Florence, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), epitomizes the Renaissance ideal of expressing infinite concepts through finite means.

The design philosophy of the Pazzi Chapel aligns with Alberti's definition of beauty derived from Vitruvius: "A harmony in which all parts are so well adjusted that any alteration would only worsen the whole." Such perfection could only be achieved by an extraordinary architect. From the late 15th century, the Pazzi Chapel was overseen by Brunelleschi.

In 1429, Andrea Pazzi, a leader of a wealthy Florentine family enriched by trade and banking, commissioned Brunelleschi to design an addition to the Santa Croce Monastery, combining a chapter house and a family chapel. However, by the time of Brunelleschi's death, little progress had been made, and there were signs of other influences, especially in the exterior design. This chapel sparked a rare medieval debate about architectural attribution, a dilemma arising from the new attitude toward architecture and the distinction between artists and craftsmen, architects and builders.

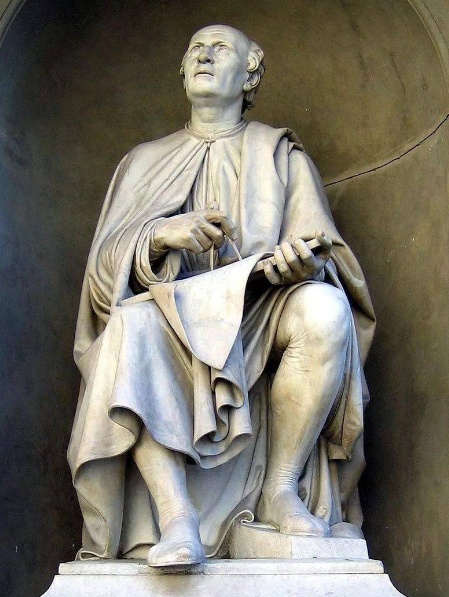

While the two architects of St. Lorenz’s Choir, Konrad Heinzelmann and Konrad Roritzer, are documented, it is impossible to attribute specific stylistic elements to either of them. They remain mere names. Conversely, Brunelleschi's personality and achievements are well known. He was the first of a new breed of architects, never apprenticed to a master mason. As the son of a wealthy Florentine notary, he received a well-rounded education.

In 1418, he collaborated with sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti to propose an ingenious engineering system for constructing the dome of Florence Cathedral without wooden centering, a remarkable technical feat. However, before this project commenced in 1419, he was commissioned to design the Foundling Hospital in Florence, often cited as the first Renaissance building. In 1421, he began work on the Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence, featuring Corinthian pilasters and a pure geometric space with a hemispherical dome atop a cubic base, foreshadowing later Renaissance central-plan structures.

Brunelleschi received considerable acclaim in the 15th century for both his engineering skills and his revival of ancient architectural forms. Architect and theorist Filarete praised him for "reviving ancient architectural styles in our city of Florence so that today, churches and private buildings no longer use any other style." According to Filarete, this revival occurred because ancient styles were "correct," and adopting them was akin to literary efforts to recreate the classical styles of Cicero and Virgil.

It is said that Brunelleschi visited Rome, making him possibly the first artist since antiquity to study ancient architecture firsthand. However, the reasons for the 15th-century revival of ancient forms and motifs are likely more diverse and complex than Filarete presumed. For instance, Brunelleschi found a system in Tuscan Romanesque architecture to construct a visible structural framework.

Gothic style is often associated with the North, and at the beginning of the 15th century, Florence's independence was threatened by Giangaleazzo Visconti of Milan, allied with the Holy Roman Empire. His death in 1402 not only removed the threat but allowed Florence to expand along the Mediterranean, elevating it from a city-state to a regional power.

During this prosperous period, Florentines proudly reflected on their origins, viewing Florence as a colony of republican Rome. Humanist and historian Leonardo Bruni wrote, "I believe this explains why, among all peoples, the Florentines have always valued freedom the most and are the strongest enemies of tyrants. Other peoples were founded by fugitives or exiles or peasants or obscure individuals, but your founders were Romans, conquerors and rulers of the world." Northern European royalty and nobility could trace their lineage to Gothic chieftains who conquered Rome; however, the commercial leaders of the Florentine Republic found a nobler ancestry in ancient Rome itself. In this context, Brunelleschi’s rejection of Gothic style in favor of Roman columns, arches, and rectangular windows was not just an aesthetic choice.

Another equally significant and far-reaching achievement by Brunelleschi was linear perspective. While various methods to suggest distance had been used in painting and drawing, Brunelleschi developed a systematic approach to scientifically measure and depict distance. Starting from the assumption that visible rays of light follow geometric straight lines, he realized that a painting viewed as a window between the viewer and the scene would adhere to these rules.

The key to his method was that all parallel lines extending into space would appear to converge at a central vanishing point on the viewer’s horizon. These orthogonal lines created a geometric framework defining the painting’s space. Brunelleschi demonstrated this system in two now-lost paintings, while his friend Alberti detailed it in his 1435 treatise on painting.

Brunelleschi’s invention was enthusiastically embraced, elevating painting to a science and opening the door to modern perspectival illusionism. This technique allowed for the realistic depiction of objects in space from a fixed viewpoint and seemed to impose a rational order on the visible world.

Notably, Brunelleschi was not just an architect but also a versatile engineer and inventor. Beyond his architectural achievements, he designed complex machinery and war devices, showcasing his exceptional talents in engineering and technology. The hoist system and rotating crane he used in constructing the dome of Florence Cathedral exemplify his innovative spirit and deep understanding of mechanical engineering.

Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel and his innovations in linear perspective marked significant shifts in architectural and artistic paradigms. These achievements reflected the Renaissance’s rediscovery of harmony, proportion, and classical ideals, symbolizing a broader cultural revival. This spirit continues to influence our understanding of beauty, order, and the infinite potential of human creativity. Brunelleschi not only left us with countless architectural treasures but also laid the foundations for modern architecture and art through his innovative thinking and technical accomplishments.