Pieter Bruegel the Elder (circa 1525 or 1530 to 1569) is a unique figure in the history of Flemish art. During the 16th century, many Flemish artists traveled to Rome and, influenced by Italian art, adopted a flamboyant Italianate style that won favor with the Church and government. However, Bruegel chose a different artistic path.

Initially, Bruegel illustrated moral lessons for engravers, with a disturbing and grotesque sense reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch. Although his early works exhibited Bosch-like grotesques, over time, Bruegel's style became more direct and straightforward. However, this apparent directness often led to misunderstandings, and his works rarely received proper appreciation. Consequently, he earned nicknames like "Peasant Bruegel" and "Jester Bruegel."

Despite his seemingly naive and innocent appearance, Bruegel's understanding and creation of art were deeply thoughtful. Like other Flemish "romantic painters," he was well-versed in Italian art but deliberately opposed prevailing styles. Living in Antwerp for most of his life, Bruegel was an important member of an intellectual community that included the great scientific inventor Christophe Plantin and Abraham Ortelius, who was planning the first modern world atlas.

Bruegel mainly created works for discerning private collectors, and shortly after his death, his paintings were acquired in large quantities by Rudolf II. In an obituary, Ortelius praised Bruegel for his fidelity to nature and noted that "his works always concealed deeper meanings."

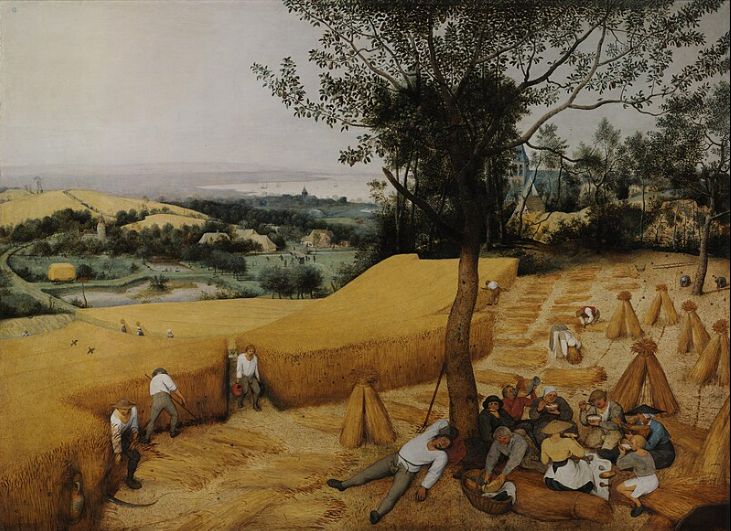

Among his works, the series of paintings depicting the cycle of the seasons stands out. While the theme was common in medieval art, Bruegel presented it in a novel way, adopting large formats typically reserved for religious or mythological scenes. His paintings are essentially landscapes and atmospheric renderings rather than illustrations of "monthly labors." For instance, in "The Harvesters", he used saturated browns and yellows to evoke the scorching heat of August fields, with details so realistic it is hard to see the scene as fictional.

Bruegel learned much from Italian art, particularly the Venetian school’s atmospheric perspective and elevated viewpoints. However, his figures were far from the poetic Arcadian residents; they were real-life peasants, depicted with realism and earthiness. In "The Harvesters," some are busy harvesting and bundling grain, while others are eating and drinking, with one peasant even dozing under a tree. These realistic scenes reflect Bruegel's keen observation and understanding of real life.

Another notable work, "The Blind Leading the Blind", showcases Bruegel’s unique artistic vision. This painting depicts several blind men supporting each other, symbolizing the struggle of humanity in ignorance and folly. The peasants' vacant expressions and awkward limbs seem to mock their comical side, but in reality, Bruegel used the lowest social class to represent all of humanity, showing deep social concern.

Bruegel's paintings express his profound understanding of humans and nature. Unlike the human-centered art of the Italian Renaissance, his works celebrate the grandeur of the universe, denying humanity a central position. Yet, his peasants remain independent individuals, living their own lives, revealing another layer of meaning in all his mature works.

Bruegel had direct contact with Dutch ethicist Dirk Volckertszoon Coornheert, a leader of so-called liberalism or spiritualism. This religious thought focused on personal relationships with God and the responsibility to overcome sin due to human ignorance. Bruegel was likely a Catholic, but his worldview was closer to Protestantism than any great artist of the 16th century, except for Dürer and Holbein. Although he did not witness the worst effects of Spanish persecution of Protestants in the Netherlands, he had his wife burn many prints with potentially "too sharp satire" to avoid trouble in his later years.

As a peasant painter, Bruegel's works are filled with profound understanding of human society and nature. Through depicting peasants and rural life, he expressed a concern for the real world while conveying deep moral and philosophical reflections. Bruegel's art transcends time and space, becoming an eternal classic.