Ancient people had a profound interest in astrology, which permeated both daily life and the realms of art and science. Court astrologers were common, responsible for selecting auspicious times for significant events. Although early Christians condemned astrology, it saw a resurgence in 12th-century Europe, quickly becoming influential enough that the Church had to adopt a tolerant stance. Despite the planets and stars being named after pagan deities, it was widely believed they revealed God's will, thus aligning astrology, astronomy, and Christian theology.

During the Renaissance, artists frequently incorporated elements of astrology into their works. The San Lorenzo Church in Florence serves as a prime example. The dome above the altar in Brunelleschi's Sacristy accurately depicts the positions of stars over Florence on July 9, 1422, the day the altar was consecrated. A similar celestial map can be found in the Pazzi Chapel. These depictions of constellations were more than mere decoration; they reflected contemporary understanding of cosmic order and belief in astrology.

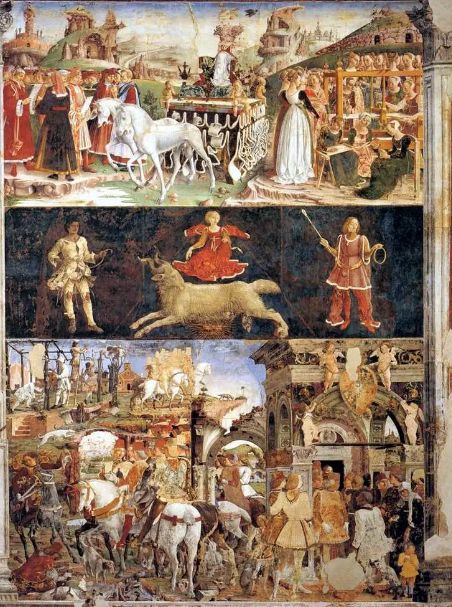

Another notable example is the Palazzo Schifanoia, the summer residence of Duke Borso d'Este of Ferrara. The palace's walls are divided into 12 sections, each representing a month of the year, painted by the chief court painter Cosimo Tura and other artists. Each section illustrates content from an astrological poem, combining elements of scholarship, craftsmanship, and astrology. For instance, Francesco del Cossa’s painting "March" depicts the goddess Minerva on a triumphal chariot, symbolizing the patroness of knowledge and craft. Each section showcases activities appropriate to the month, such as courtiers hunting and farmers pruning vines, with Borso d'Este encouraging the execution of justice, all closely related to astrology, reflecting a harmonious universe.

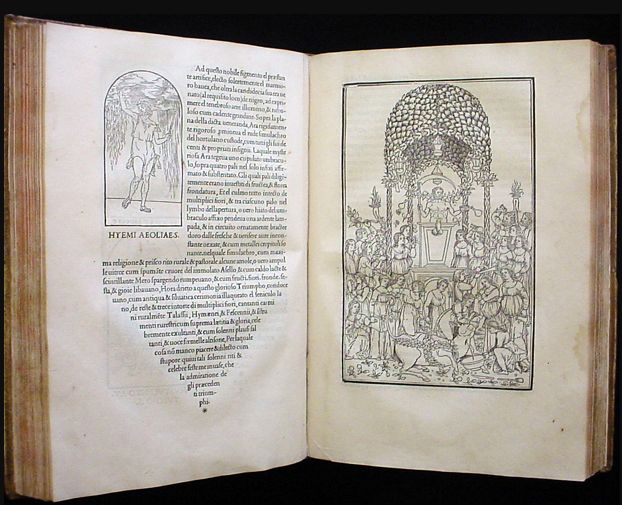

Humanists had varying views on astrology. While some opposed its fatalism, believing in human agency, many scholars were drawn to the ancient mysteries, convinced that eternal truths lay within them. This is exemplified in Francesco Colonna's allegorical romance "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili", written around 1460. The book combines literary and artistic expression of these mysteries, featuring intricate woodcut illustrations, and was published in Venice in 1499. This work not only showcases the period's fascination with astrology but also merges mysticism with scientific and aesthetic elements, representing the era's intellectual spirit.

Renaissance astrology not only influenced artistic creation but also propelled scientific advancement. The depiction of constellations and astrological elements in artworks reflected contemporary understanding of cosmic order and illustrated the close connection between art and science. This relationship fostered the cultural flourishing of the Renaissance and laid the foundation for future developments in both fields. By portraying celestial bodies and astrological themes, Renaissance artists combined mystical cosmology with scientific inquiry, producing works of both aesthetic and scientific significance.