In the early 17th century, the art of Rome was revitalized by the contributions of two artists from northern Italy: Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) and Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi, 1571-1610). Although they are now seen as creators of two distinctly different styles (idealism and naturalism), they were both highly praised at the time, often by the same critics.

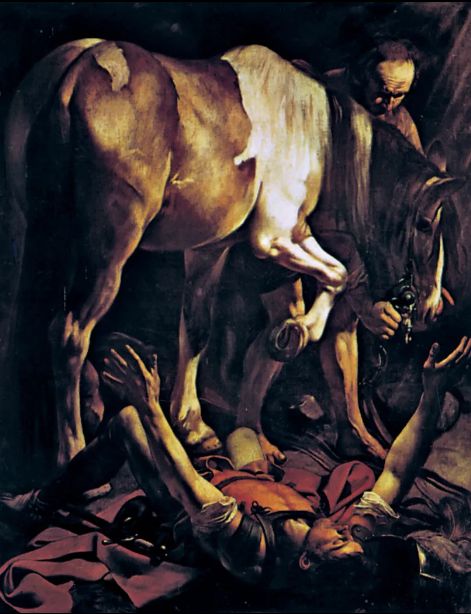

In 1600, a church lawyer commissioned the construction of a funerary chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Annibale Carracci was responsible for the altarpiece, while Caravaggio painted two works for the side walls. One of Caravaggio's works, "The Conversion of St. Paul," exemplifies how realism had thoroughly replaced the symbolism of earlier religious art. In this painting, there are no exaggerated contrasts or stylized "artistic figures" typical of mid-16th century Mannerist painters. Instead, Caravaggio directly depicted the miraculous conversion of Saul, a persecutor of Christians, to St. Paul. Caravaggio seemed to adopt the robustness and confidence of High Renaissance art while discarding its idealization.

In "The Conversion of St. Paul," St. Paul is portrayed as a young, rough soldier with a beard. His steed is a strong, mottled horse led by an old, wrinkled, bald man. This strikingly realistic depiction of the old man, reminiscent of a peasant, also appears in Caravaggio's later works and caused quite a sensation at the time. Although the painting's illusionistic technique shows a raw characteristic, it cannot be termed purely realistic. The painting accurately conveys the "miraculous" nature of St. Paul's conversion, with the saint's hands outstretched to embrace the blinding light piercing his heart and eyes.

Caravaggio was well aware of the teachings of St. Ignatius Loyola in his "Spiritual Exercises," which emphasized obtaining spiritual understanding through the senses rather than intellect. His painting, using life-sized figures of ordinary people, invited viewers to partake in the mystical experience of the saint's conversion. The best way to view this dramatic piece is to kneel at the chapel entrance.

Three years after the completion of this work, Dutch painter and writer Karel van Mander (1548-1606) published a report detailing Caravaggio's "great works" in Rome. He praised Caravaggio's dedication to nature, stating, "He considered all other works insignificant, like children's doodles, regardless of their subject or creator, unless they portrayed life itself. Aside from imitating nature, all other techniques were useless. He never put brush to canvas without thoroughly studying the subject". This idea contradicted other 16th-century art theories but was seen by van Mander as an exemplary model for young painters, leading to the spread of the Caravaggesque style across Italy, Spain, France, and the Low Countries. This style, characterized by non-classical figures set against mysterious backgrounds and highlighted by dramatic lighting, quickly gained popularity.

Simultaneously, Annibale Carracci's work style also gained recognition, especially in his frescoes at the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Like Caravaggio, Carracci broke away from traditional styles. His first biographer, the influential art theorist Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1613-1696), credited him with rescuing painting from the confines of Mannerism. Inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, Carracci rationalized the structure and clarified the boundaries between different levels of reality. His decorative framework used illusionistic techniques, featuring stucco and bronze medallions with male figures, utilizing foreshortening to make the light appear to come from a real source below. His narrative scenes depicting the divine power of love seemed to be framed paintings set within the decorative structure, a style influenced by Raphael and ancient sculpture.

Carracci's method of work was markedly different from Caravaggio's. To create the Farnese ceiling frescoes, he made over 500 sketches. He and his brother Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) and cousin Ludovico Carracci (1555-1619) were tireless draftsmen, drawing everything from composition studies and studio models to street scenes and caricatures. They would even sketch during meals, with one hand holding bread and the other a charcoal stick. Their goal was fidelity to nature, purified and refined. To achieve this ideal, they turned to ancient sculptures and Renaissance masters for guidance. Though Annibale Carracci was not a theorist, his works were praised for embodying the aesthetic theories of the 16th century, laying the foundation for academic teaching for the next two centuries.

In the 1580s, the three Carracci brothers gathered a group of artists in Bologna to form the "Academy of the Beginners" (Accademia degli Incamminati). This informal group provided a quiet and studious environment for discussing problems and practicing drawing, contrasting the noise of the traditional workshop. The term "academy" at that time implied a guild or association of professionals. The first artist academy was established in Florence in 1563 with similar ambitions to help painters and sculptors escape the strict regulations of the craft guilds. These types of academies were combined in the Academy of St. Luke in Rome, founded at the beginning of the 17th century. The Academy of St. Luke began offering lectures on art theory, guidance in design, and facilities for life drawing classes to supplement workshop apprenticeships. Similar academies were later founded throughout Italy and northern Europe, with the most famous being the Academy in Paris, making art education more systematic than elsewhere.

With the rise of academies came a widespread interest in art collecting in the 17th century. Collections included works by ancient masters and contemporary artists, naturally leading to the art market's growth. This shift moved the focus from large murals and traditional forms to more portable and transferable easel paintings, which became the most important works in European art. This phenomenon is unique and not found in other cultures. Collectors such as Charles I of England, Philip IV of Spain, exiled Queen Christina of Sweden, Cardinal Mazarin, and Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria amassed significant collections. Part of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm's collection was documented through paintings: in a room filled with artworks, Giorgione's "Three Philosophers" is on the right side of the painting, with works by Titian and other Venetian artists above it. Raphael's "St. Margaret" is next to Rubens' large sketch "The Circumcision." In this context, religious images, portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and historical scenes were distinguished only by their gilded frames, losing their original religious significance and being treated purely as artworks. Acquiring these paintings was primarily to display status, wealth, and taste. The preference for rare and expensive works by Renaissance masters aligned with academic teachings, but by the mid-17th century, collectors began to turn to less esteemed works, such as those with imaginative or erotic themes. This shift increased the importance of these types of paintings in the history of European art.

The contrasting styles of Caravaggio and Carracci represent two significant directions in 17th-century European art. Their innovations in artistic technique and their contributions to art theory and practice had a profound impact on future generations. Caravaggio's realism and Carracci's idealism intersected in Rome, driving the flourishing of European art. Their works not only showcase their unique artistic styles but also reflect their deep understanding and pursuit of the essence of art. It was through this artistic interaction and integration that 17th-century European art reached new heights.